I once met a woman who fancied herself artistic. Upon learning of my vocation she puffed with pride, she had something to tell me. She had visited a number of art museums and noticed that all portraits (self-portraits) of artists were the same in one regard. All the artists were left-handed. As she was left-handed, she saw this as evidence of her innate creative prowess. She asked if I was left-handed, and when I responded in the negative, her raised eyebrow spoke of an air of ‘good luck with the art thing kid.’ What this lefty-supremacist failed to realize was that her theory was born through a looking glass. Most of the self-portraits you have seen (up to the birth of photography, when an artist could use a photo as a reference) are the reverse of reality. The self-portrait painter uses a mirror to see himself. Most artists probably, as most people, are right-handed.

The self-portrait is an entirely unique kind of portrait. Indeed it is unlike any other kind of representational painting. An artist depicts the world he sees. If I want to paint a lovely tree or person, I undertake the process of imitating the subject on canvas. But when the artist decides to depict himself, what does he paint? The problems involved with this endeavor become more complex than the distortion of the mechanism of mimesis (the mirror and the mirror image) and envelope issues of self identity-epistemological implications that wind into an intellectual gordian knot. I won’t begin to fray a strand of this philosophical riddle here, but I do hope to ask: what does self have to do with portraiture?

Perhaps the inner dialogue best describes what we think of as our self? In his novel Portrait of the Artist of a Young Man James Joyce masterfully narrates a subjective self-portrait. This bildungsroman (coming of age novel) employs the narration of an inner dialogue of Stephen Dedalus from the childish: “Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo” to the sophisticated thoughts of a introspective, curious adult. The growth of an identity, the struggles that that entails, is the arc of the book. Joyce is creating a verisimilitude inner portrait of his alter ego in this book. The subjective experience-the self-portrait, is at the core of what the book is about.

So how do I paint myself? How do I look to myself? I have known my beautiful wife for five years now; a relatively short amount of time. There is no doubt, however, that I have spent more time with her face than the face I have endured 24 hours a day for 45 years. Gratefully, I am assaulted with my visage at the most two minutes a day. One would think our faces are utterly familiar to ourselves, we spend our life with our faces, but we really rarely experience the person in the mirror. And, as we have seen, this isn’t even how the rest of the world sees us anyway. No, it is our bodies - in a Cartesian ghost-in-the-machine way - that we experience ourselves in a visual way. I look down and I see my hands; to my horror I see white chest hair; this image; these things of sight, this is the Mason that Mason is most familiar with.

Pain is a phenomenon which is entirely ours. In her seminal work The Body in Pain Elaine Scarry discusses what is an entirely subjective phenomenon. “Whatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unsharability, and it ensures this unsharability through its resistance to language.” Pain is our most intimate of experiences, the only audience of its effects, ourselves. Pain drowns out all other noise and thoughts of our existence, and makes itself central. Pain is the toddler on the airplane screaming that your noise-cancelling headphones will never begin to silence. As Scarry describes it, “It is the intense pain that destroys a person's self and world, a destruction experienced spatially as either the contraction of the universe down to the immediate vicinity of the body or as the body swelling to fill the entire universe.” In other words, our experience of pain focuses. Our world becomes that pain. The subjective experience of our self is most intensely felt in pain. When we have a toothache, there is no doubt who that tooth belongs to; and my entire world is that tooth. In pain, the face in the mirror ceases how we identify self, the pain becomes us. Which brings me to The Artist Foot

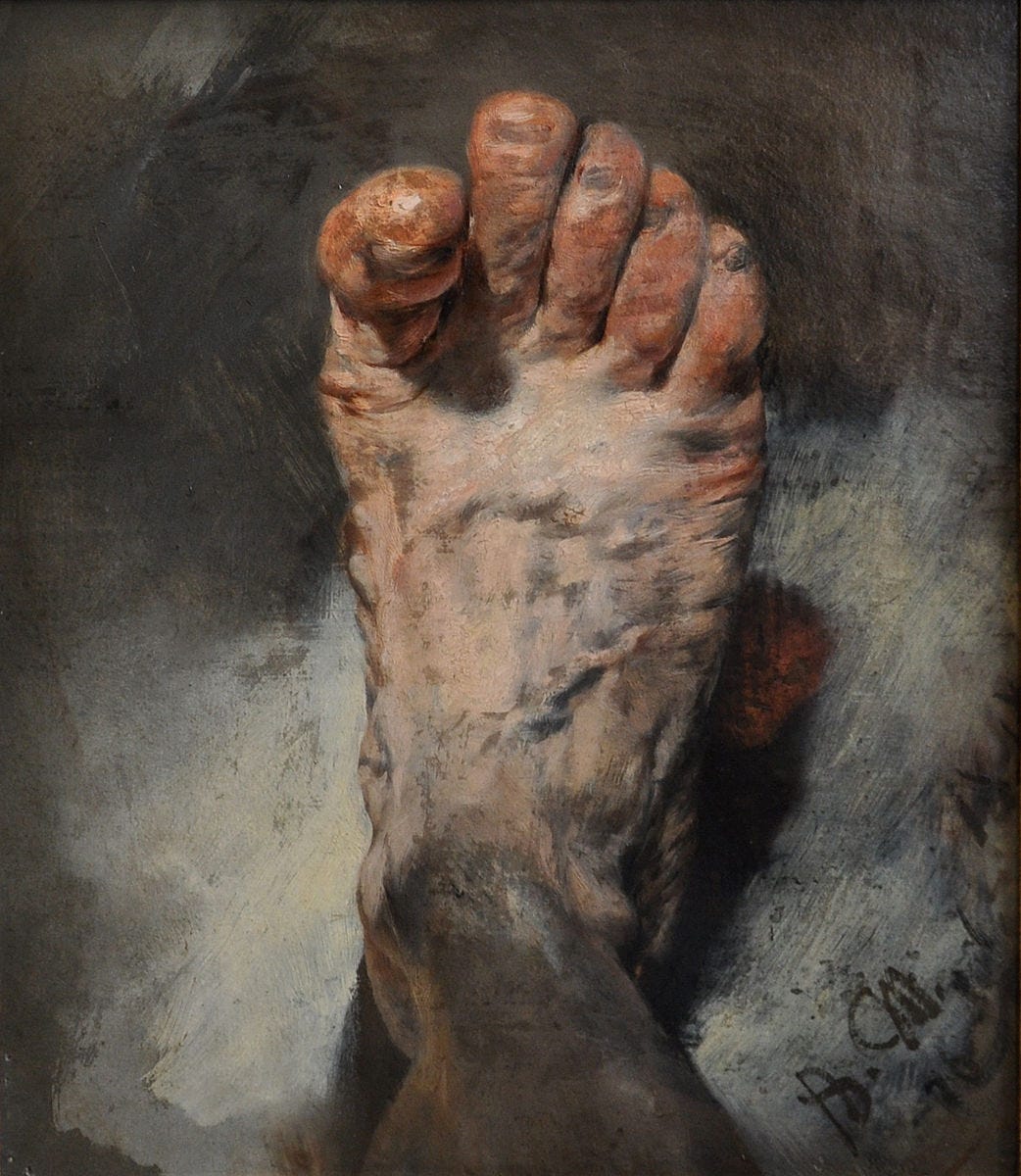

The Foot of the Artist, Adolph Menzel. 1876

Adolph Menzel was one of the most prominent artists of nineteenth century Germany. He gained wide acclaim for his realistic and dramatic history paintings. His paintings possess a rare emotional depth that is commonly absent from that genre. A French dermatological paper was published in 2019 entitled, The Artist's Foot by Adolph von Menzel (1876): A realistic portrait of dermatoporosis and venous insufficiency. If this article was right and the painting actually depicts a skin illness affecting the artist’s foot - a condition that would certainly be painful - then this pain would be enough to monopolize the thoughts of the artist. One could picture the artist (who was notably insecure about his height (4’6”) and his large head) looking down at his veiny discolored foot. Perhaps Menzel saw this image as the essential him at the time. More him than his face.

Our stories are most verily told in our face. There is no doubt in my mind that a person's eyes speak more of their biography than we can fully grasp. It is important to remember how we see ourselves is commonly belied by our face. As the Cliff Richard song goes, “Your Eyes Will Tell On You.” The stories we tell to ourselves are rarely more accurate than those we tell to others. Those who prize self scrutiny and exploration, embark on a journey of vicissitudes and illusions. Sussing-out who and what we are is the great challenge and project of our lives. Depicting self should be respected for the odyssey that that word entails.

Thanks for the Adolph Menzel lead. Hate to be a downer, but after an image search, I discovered there’s a whole slew of scumballs selling posters/canvas prints of his paintings in the $25-$100 range. I can imagine some "artistic" real estate agent scooping up one of the framed bargains to hang in a FOR SALE suburban McMansion. Maybe I’m wrong, but I’m assuming the “wall art” sellers are paying no fees to the owner of the original painting.

“Explore more than 406,000 hi-res images of public-domain works from the The Met collection, all of which can be downloaded, shared, and remixed without restriction.”

https://www.metmuseum.org/policies/image-resources

Speaking of “self”, if you haven’t yet seen it, the 2002 British TV series The Century of Self is interesting.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jymMjNc0igI

My Sunday Morning, "Eye Opener"... Thank you.