A funny thing about Monet

When you consider the complexity of the visual world, the way our eyes and mind process it is nothing short of miraculous. The amount of information that we are presented with requires a herculean level of sorting to absorb and make sense of it all. The mechanics of the way our minds process sensory information provides ample fodder for neurological and psychological theory. In the world of art, the question of sorting is dealt with practically.

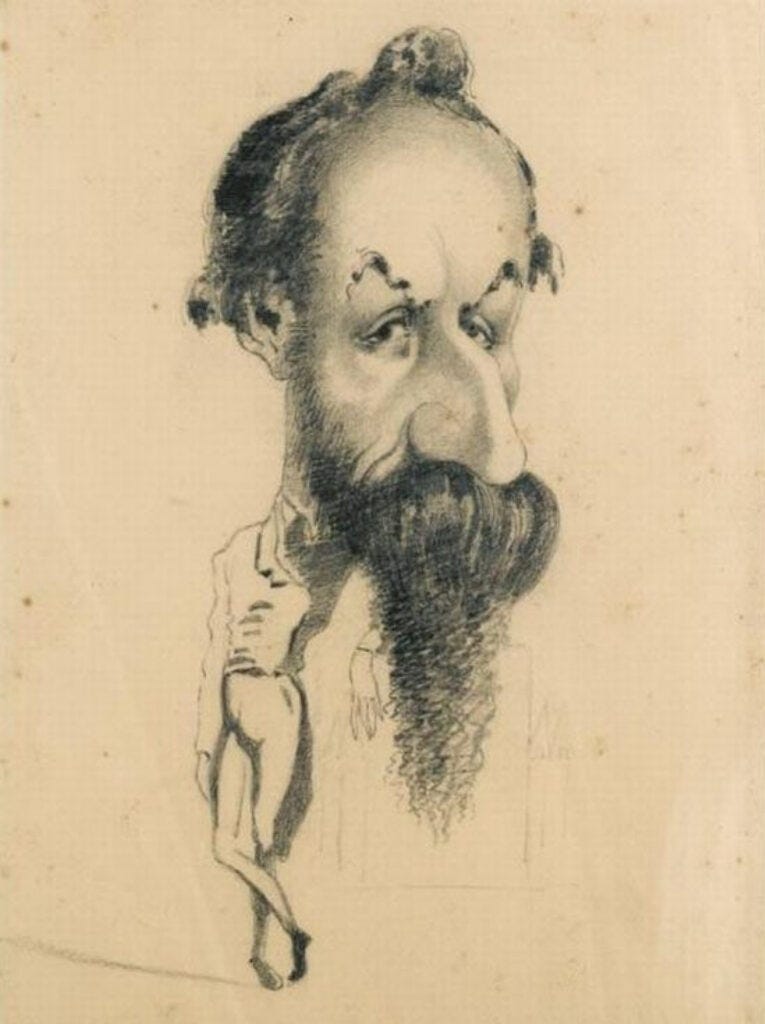

Caricature of Philiberte Audebrand, Claude Monet. 1858

In the mid-nineteenth century, a young art student began drawing caricatures of his friends and acquaintances for cash. He did these for a couple years before beginning to draw the landscape ‘en plein air’ (outdoors). His caricatures are relatively unremarkable. They don’t herald a great talent, they are just caricatures. The grotesque exaggerations may speak to the unique peculiarities of the chosen subject’s countenance, but to us, who are unfamiliar with the drawings’ targets, the comical hyperbole is meaningless. It is a good thing that this inchoate artist dropped the caricatures and focused his attention on painting in the outdoors, because what would come from his brush would be brilliant. It was his revolutionary depiction of the outside-world that Claude Monet is remembered for, but perhaps the caricatures had something to do with his artistic development outside of just being a good side hustle.

What is a caricature? A portrait of sorts, its main defining characteristic being exaggeration. This exaggeration is almost always implemented as a means for humor. It is intuitive - yet highly buzz-killing - to point out that exaggeration is a key component of comedy: “I haven’t spoken to my wife in years. I didn’t want to interrupt her.” “I was so ugly my parents had to hang a pork chop around my neck to get the dog to play with me.” Rodney Dangerfield understood the principle of exaggeration’s centrality to comedy, but artistic comic satirists - or caricaturists, realized this far earlier.

The first political caricatures date back to at least the 18th century. But perhaps their antecedents are myths where moral imperfections are visited as physical abnormalities. This can be seen in the Greek myth of Priapus (I’ll leave it to you to discover what abnormality he was cursed with). What comics and caricature creators have in common is they notice a key feature and exploit (exaggerate) it to the desired effect. By the time Monet was drawing his caricatures, the formula had settled into place. Caricature also hasn't changed, the ones Monet drew could have been drawn on Coney Island last week. Like those before him and those today, when Monet saw a man with a relatively large nose he inflated it; ears the same; small eyes became dots. This isn’t high art, but it takes a certain talent for noticing.

The Oxbow, View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm, Thomas Cole. 1836

Contrary to popular opinion, quite a while before Monet, French painters had painted directly in the outdoors, but these earlier artists tried to refine their paintings to a high level of detail. The relatively punctilious French artists were nothing close to the Americans who endeavored to paint in rigorous exactitude at the same time idealizing the scene for dramatic effect. Take for example the paintings of Thomas Cole. A canvas of his could provide a passible education on the floristics of a chosen scene. Artists like Cole would make studies of the scene they planned to paint and return to the studio for the final painting. This method allowed for a painstaking attention to detail in a controlled environment. With plein air paintings there is no time to fritter over every leaf. All information has to be recorded before the conditions of the environment (eg. weather, light) change.

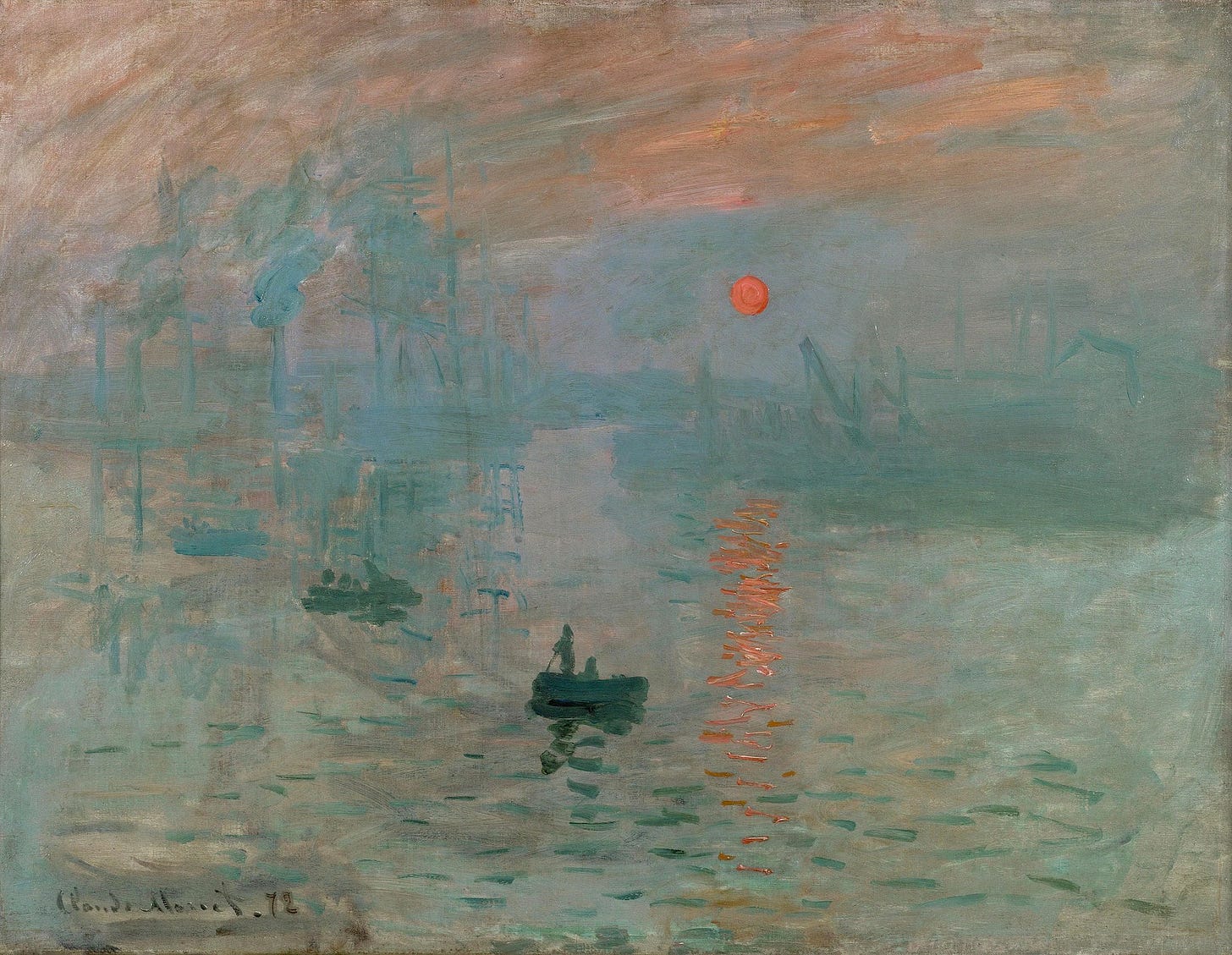

Impression, Sunrise. Claude Monet. 1872

A group of artists disaffected and rejected by the hierarchy of the French art-world found common purpose and dubbed themselves Société Anonyme des Artistes Peintres, Sculpteurs, Graveurs. They staged their own exhibition in 1874. At this show, Monet exhibited his painting Impression, Sunrise. The critic Louis Leroy used the title of this painting to disparage the group of artists whom he dubbed Impressionists. What he saw as unfinished sketching or slap-dash compared to the rigorous academic art of the previous regime, appeared spontaneous and energetic to those who recognized the style and its visually gnomic qualities. The constant change of light - the reason why other artists resisted painting in the environment - was what the Impressionists tried to capture. The strong suit of the impressionist and Monet in particular is the power to cut the fat from details, to draw out the most important features.

What is critical for plein air painting - and for that matter, even the exhaustively detailed paintings of Cole - is an ability to sort. The mind must sort what it sees and mark what is important to depict. All of this information has to be recreated by the hand. When the hand is rushing to record what the eyes are seeing, only what is most salient can be acknowledged. A real time editing has to occur, otherwise an artist could take years to finish a single canvas. Noticing what is important is at the core of what the artist does. This act of noticing the important is critical to the caricature artist too. The caricature artist finds a salient feature of a face and exaggerates it in order to mock it.

The operation of the old man painting in his garden in Giverny would not be much different from that of the young man drawing a caricature. The most important things received the attention and were recorded, all else would be left unattended. He took the world as he saw it and simplified it. The ability to notice and edit is a critical talent, whether we’re talking about Rodney Dangerfield or Monet.